Nand 2 Tetris

Nand2Tetris is a freely available, online course which teaches you the basics of logic gates & builds up from there. You create the chips required for a computer, build an assembly language assembler, a high level Java-like language, OS abstractions & finally programs like Tetris.

This is going to be my reports of completing the course including:

- How is the course structured?

- What did I think of it?

- What were the things I found most useful from it?

- What challenges did I face along the way?

In case it sounds interesting already the course is available as a book, The Elements of Computer Systems, but is also freely available through Coursera which is a hugely generous thing for it’s creators to do 👏

The course is split into 2 modules:

- NAND gates to a computer with an assembly language

- A virtual machine abstraction to high level programs written in an OOP language

I’ll cover each half separately.

Part 1 - Building a computer from scratch

Part 1 covers:

- Basic logical operations e.g. AND gates & OR gates from NAND

- More complicated gates such as Adders & Increment & ALU (Arithmetic logic unit)

- Memory units such as Bits, RAM & Registers

- Building a CPU then putting it together to build a computer

- Writing assembly

- Writing an assembler to convert assembly to binary

This was the most interesting half & you can quickly experience going from a few simple gates to a working computer. The hardware description language (shown below) is very simple but you quickly go from And gates to ALUs.

CHIP Or {

IN a, b;

OUT out;

PARTS:

Nand(a=a, b=a, out=nand1);

Nand(a=b, b=b, out=nand2);

Nand(a=nand1, b=nand2, out=out);

}

You become very familiar with truth tables & binary logic to the point where you start to see how conditional logic can be implemented in binary

| a | b | out |

| --- | --- | --- |

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

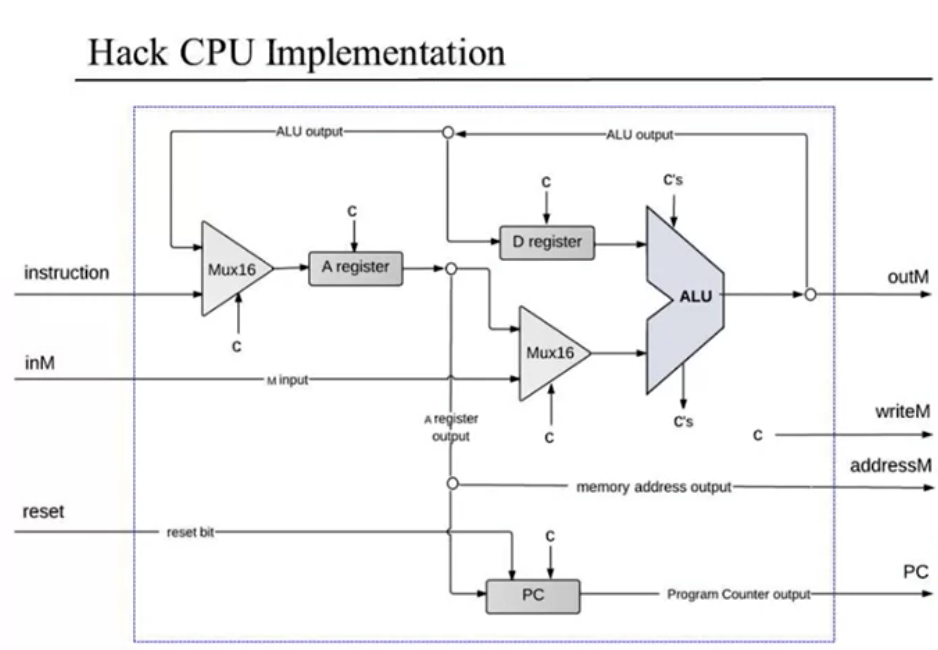

The breakthrough moment for me came with seeing how the binary assembly instructions were encoded such that a 1 or a 0 in a specific bit would trigger different parts of the CPU

When combined with the expected behavior of the jump bits (0-2) it begins to make sense how you add simple gates to control the behavior of the program counter register.

1 1 1 a c1 c2 c3 c4 c5 c6 d1 d2 d3 j1 j2 j3

j1 - j3 = jump bits

| jump | j | effect |

| ---- | --- | ------------------ |

| null | 000 | no jump |

| JGT | 001 | if out>0 jump |

| JEQ | 010 | if out=0 jump |

| JGE | 011 | if out>=0 jump |

| JLT | 100 | if out<0 jump |

| JNE | 101 | if out!=0 jump |

| JLE | 110 | if out<=0 jump |

| JMP | 111 | unconditional jump |

Part 2 - Everything else is just software

The 2nd part covers:

- Building a virtual machine abstraction on assembly (similar to Java or C#’s bytecode)

- Building a compiler for an object oriented language

- Writing operating system functions

- Writing a simple user-level program in the new language

This half took considerably longer, partially because we had a baby while I was working on it 👨🍼, and I think there were less new concepts to take away. Building compilers is something I have done before in other projects so there was little new there although this was the closest I’ve come to building a working language.

class Main {

function void main() {

var Array a;

var int length;

var int i, sum;

let length = Keyboard.readInt("How many numbers? ");

let a = Array.new(length); // constructs the array

let i = 0;

while (i < length) {

let a[i] = Keyboard.readInt("Enter a number: ");

let sum = sum + a[i];

let i = i + 1;

}

do Output.printString("The average is ");

do Output.printInt(sum / length);

return;

}

}

This Jack language was missing a lot of features which is why the second half of the course, creating the operating system, using Jack was an exercise in frustration. Building a memory manager to provide malloc & free like functions was very tough with a language that didn’t have any debugging tools or even simple things like if, if else, else or break 😬.

That being said there were still things I came to appreciate, not because they were part of the course but because the course gave me a great chance to think about them. A good example of this is strings. The Jack language has a String type managed by the operating system. The course expects String literals to be of type String, to allocate memory but does not mention cleaning them up. This was the catalyst for me understanding why string literals are const char* in C++ & not string with the same thing being true in Rust. It’s taken years for me to finally understand the difference between &str & String.

Challenges

There were 3 main challenges I faced during the course. I faced these all while working on second part of the course which is probably why it took longer & why I found part 1 more fun.

Debugging

The main challenge was debugging issues. There are several layers involved in getting software working:

- Assembly/CPU

- VM layer

- Jack language

- Operating system

- User level code

If there is a bug in user level code it could be caused by a number of factors & any effort to debug starts of with removing layers to try to track down the bug. Once you have tracked down the issue to a specific layer you often have to debug across languages. You might have some Jack code but can only debug the VM output or you have some VM output but can only debug the assembly.

When debugging across layers I’ve found it necessary to create source maps. These can be as simple of adding the source line into compiled output as a comment or it might be a file which explains where a line of code came from & provides values for assembly labels. Without these debugging takes much longer & it’s something that I’ve come away with a new appreciation for.

The Jack language

The simplicity of the jack language is great for implementing a compiler but makes it a horrible language to write code in. There are a few features that I’ve taken for granted:

breakif, if-else, else- block scoped variables

!=

Some of these were so bothersome that I ended up implementing my own version. Locally scoped variables with extremely bothersome so I built that into the language as I went because I knew I would need it and break turned out to be almost required for the memory manager & tracking through linked lists.

It’s a rare language that makes me appreciate the richness of C!

Image data

This is a small one but implementing screen data as bits with 16 pixels making a word (the computer is strictly 16-bit) makes games extremely difficult to build. Smoothly moving a sprite in the X direction involves it sitting over a word boundary at some point. If you store your sprite as bytes instead of pixels (you’d do this for space reasons) you would need to bit-shift the bytes in order to move them a pixel in the x direction.

The main issue is that the computer does not support hardware bit shifts so to encode an animation you need to render your sprite multiple times. My demo application needed to do this so I had to write some Python in order to generate th Hack code.

Older games consoles got around this using the concept of sprites which could be positioned on the screen & would be rendered using either hardware or an OS function & without this Hack is a horrible platform to make any game more complex than Tetris which is a shame.

My overall thoughts

I think Nand2Tetris is a great course which will teach a lot about the fundamentals of computers. It’s not for those with a small amount of free time though & unless you were really interested in high level programming languages (which you probably aren’t if you’re going through a course on building a computer with just NAND gates) I would only recommend doing the first half.

I have enjoyed the process of completing Nand2Tetris though & can’t thank the creators enough for putting it together & making it available.

Footnotes

The banner has been provided by https://www.nand2tetris.org/ under the Creative Commons license