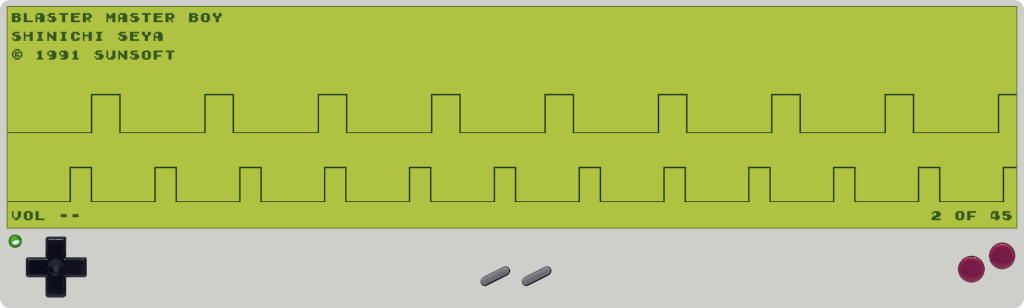

Gameboy First Sounds

Getting audio working is one of the hardest parts of emulation. Unlike graphics, which can be broken down into frames & pixels, audio doesn’t neatly break down. Recently, I managed to get the boot ROM sound (video linked below) working in my Rust emulator Rust GB so I thought I’d share my notes on this specific sound and how it can be implemented.

Warning: The article below details my understanding of Gameboy audio at time of writing and could be completely wrong.

Introduction to Gameboy Sound

The gameboy has 4 audio channels:

- Square 1

- Square 2

- Wave

- Noise

For the boot sound of the Gameboy we only need to implement the first square channel and even then we don’t need all it’s features.

What does generated audio look like?

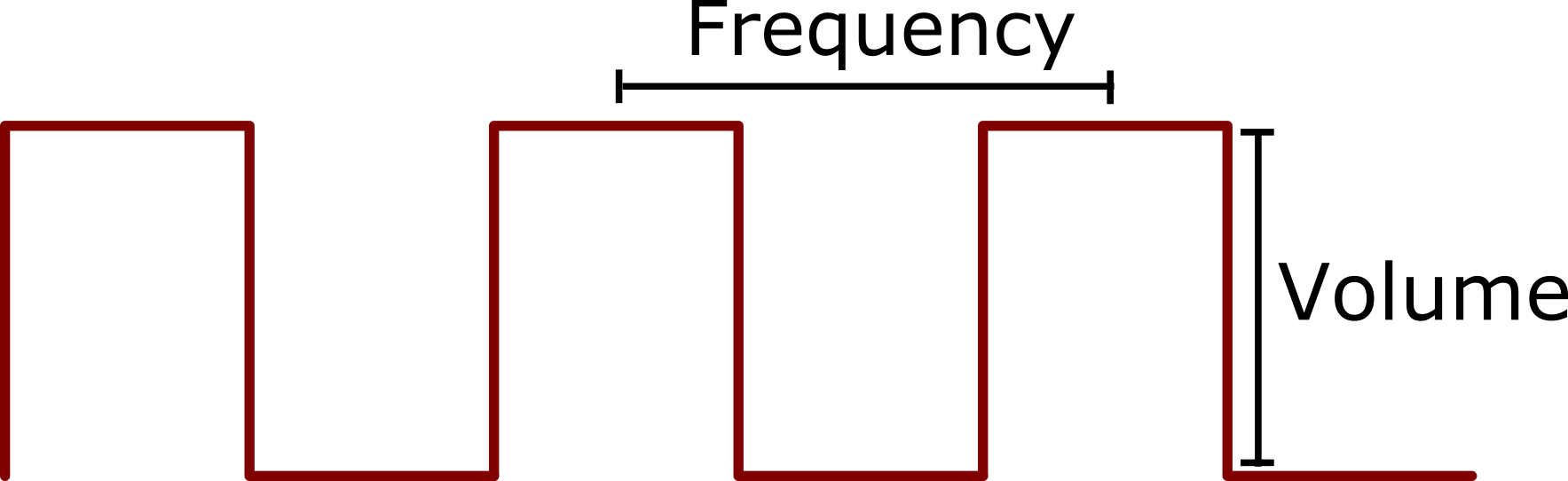

Generated sound is a buffer of values. Each value represents a volume with the distance between the peaks is the frequency.

The issue with generating Gameboy audio data is that most modern audio hardware runs at 44100Hz or 48000hz but the Gameboy outputs much faster than that. Therefore we need to do some sampling. Onto that later…

Square channel 1

To generate values we need to understand how the first square channel translates bits in memory into sound. GB dev helpfully tells us what registers make up the first channel and what values are set by each bit:

FF10 -PPP NSSS Sweep period, negate, shift

FF11 DDLL LLLL Duty cycle, Length load (64-L)

FF12 VVVV APPP Starting volume, Envelope add mode, volume envelope period

FF13 FFFF FFFF Frequency (least significant bits)

FF14 TL-- -FFF Trigger, Length enable, Frequency (most significant bits)

This seems complicated but we only need to look at a subset of data:

FF10 ---- ----

FF11 DD-- ---- Duty cycle

FF12 VVVV -PPP Starting volume, volume envelope period

FF13 FFFF FFFF Frequency (least significant bits)

FF14 T--- -FFF Trigger, Frequency (most significant bits)

All these values are implemented as 2 numbers:

- The value in the register bits

- And a ‘shadow’ value which is used once the sound is triggered.

Modifying bits once the sound has been triggered doesn’t need to do anything to emulate the boot sounds.

Duty cycle - FF11 (bits 7-8)

The duty cycle is a value of 0 - 3 which determines how long the square waves are:

| Duty | Waveform | Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 00000001 | 12.5% |

| 1 | 10000001 | 25% |

| 2 | 10000111 | 50% |

| 3 | 01111110 | 75% |

The duty cycle is represented by a count which cycles 0-7 and is incremented according to the frequency. When we come to sampling a value (see below) we will get a value of 0 or 1 by indexing the above waveform by the count e.g.

let current_waveform = [1,0,0,0,0,1,1,1];

let duty_count = 4;

let output = current_waveform[duty_count];

Frequency - FF14 (bits 1-3) & FF13

The frequency is a timer which increments the duty cycle counter. It’s initialized from a value from 0-2047 (take from the registers) calculated as (2048-frequency) * 4. The timer counts down every CPU cycle and when it hits 0 it is reset to (2048 - frequency) * 4 and the duty cycle is incremented (wrapping around at 8).

Starting volume - FF12 (bits 5-8)

The volume is a value from 0-15 which multiplies the value coming from the duty cycle to create the output volume.

Volume envelope period - FF12 (bits 1-3)

The volume envelope is another timer which decrements the volume when it hits 0. To implement the volume envelope period we initialize a timer to 65536 * the period counter and reduce it every CPU cycle. At 0 we reduce the volume by 1 and reset the timer to 65536 * the period counter.

This is what causes the fadeout of the second sound.

Frame sequencer sidebar

The volume enveloper timer is ticked at 64Hz by another timer called the Frame sequencer which itself is clocked at 512Hz. The Frame sequencer is responsible for some other timings but we don’t need to be aware of this for the boot sounds.

Trigger - FF14 (bit 8)

The trigger bit starts a sound running. When it is triggered it:

- Sets the duty counter to 0

- Starts the frequency timer (from the frequency registers)

- Starts the volume enveloper timer (from the volume envelope period register)

- Resets the trigger bit (to prevent the sound starting again)

Anatomy of the sounds

The boot sound is made up of 2 sounds:

- A lower pitched sound

- A higher pitched sound which fades out

If we examine the values in memory at the point the sounds get triggered we see the following values:

Sound 1

FF10: 0b00000000

FF11: 0b10000000

FF12: 0b11110011

FF13: 0b10000011

FF14: 0b10000111

Sound 2

FF10: 0b00000000

FF11: 0b10000000

FF12: 0b11110011

FF13: 0b11000001

FF14: 0b00000111

Which translate to the following values:

| Sound 1 | Sound 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 1923 | 1985 |

| Volume | 15 | 15 |

| Envelope period | 3 | 3 |

| Duty cycle | 2 | 2 |

From this we can see that most of the values between the 2 sounds remain the same except the frequency. This is most likely done to save space in the boot ROM sequence.

How we sample the audio

In order to downgrade from the high resolution of the Gameboy audio to the lower resolution of modern hardware we need to sample the audio. Assuming that our CPU framerate is stable we can calculate how many CPU cycles should pass before we get an audio value.

The following is code from Rust GB which calculates how many CPU cycles should pass before we get a value

const SAMPLE_RATE: i32 = 44100; // Hz

const CYCLES_PER_SECOND: i32 = 4194304;

const CYCLES_PER_SAMPLE: i32 = CYCLES_PER_SECOND / SAMPLE_RATE;

To generate a value we do the following calculation:

output = volume * current duty value

Important Caveat:

These notes are about generating audio for the initial boot sounds. There might be some things which come from a deeper understanding of the Gameboy which contradict what I’ve written. Don’t treat me as an expert!

Further resources

- A very helpful comment on reddit explaining some concepts: Reddit link

- The gbdev documentation on the audio channels: GBDev

- My emulator which runs the audio for the boot ROM Rust GB

Title image taken from: https://rmconway.com/ostrich/